My Father’s Peculiar Funeral

That my father had died was not traumatic news. It was strange. Eight years later it still is. This is a first draft that took many drafts to write of how that relationship ended.

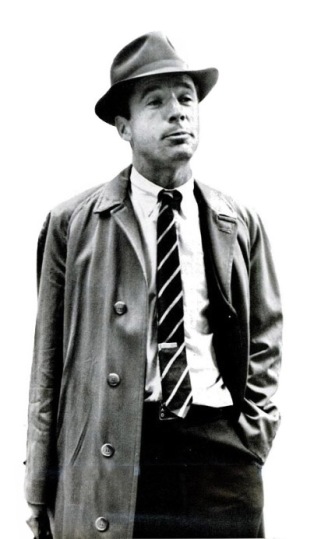

The rakish photo of him at right comes from a full page of the March 1967 Life Magazine. It was published three months before I was born. My mother saved a copy even after he left. The article about “Mr. Brain Drain” describes how this “restless 37-year-old American, … president of a New York firm called Careers Inc, which recruits personnel for big corporations,” was, in his words, “draining the English blind of their most promising talent.” He was a daring and cocksure entrepreneur (“I’ve never had to look for a job myself,” William Douglass explains.) Things went well until they didn’t. A few years later the restless man was bankrupt. Thirty-eight years later he was dead.

He was a raider not a builder. As I’ve described, my mother, fifteen years his junior, raised me alone. He left before I was born and they were soon divorced. I knew him less than slightly, not enough to miss him. He contributed nothing.

Such a story of abandonment is depressingly ordinary, and I might have dismissed his death. Yet the death of a parent is unique. I’ve observed others lose theirs and the effect can be surprising. Besides grief I’ve seen guilt for feeling the “wrong” thing or feeling too much or too little. I’ve seen two full-grown men unexpectedly cry over it while simultaneously apologizing for crying. (It’s a guy thing.) They were relieved when I assured them it was a unique loss. By the time my turn came I knew it was something I needed to think through.

His death was certainly a surprise. Cancer corroded his body for months but no one told me. The most recent contact we’d had was the year before when he phoned impromptu to ask my kids’ birthdates. I still have no idea why. We had had no contact in seven years, but he invited no chit chat. When I’d last seen him, shortly after we moved to Virginia, he’d been a healthy 60-something. His mortality wasn’t on my mind. He visited our home during a brief detour through town. It must have been a pleasure to meet his adorable young grandson, with whom he spent about thirty-five seconds. His parents were of the Victorian tradition, and he was not the touchy-feely sort. His brother once said he couldn’t remember their parents ever having hugged them.

I heard a while after the visit that he had concluded I evidently didn’t want further contact. I’m not sure what evidence I gave, considering I didn’t think that. True, I made no overtures. I’ve always been lousy about Christmas cards. It was a difficult time for me, not that he knew. He tucked his inaction within mine. But he carried the laissez-faire too far when he did not tell me he was dying. He made the choice for himself. In truth I would have liked to say goodbye to someone who could say it back. I suppose he rationalized that the silence was respectful. I actually hope he didn’t believe his own patter, that he was dishonest rather than clueless, but I don’t know.

I was notified of the death by my kindly Seattle cousin Hoby, his nephew, who happens to be a really nice guy. He said he would be flying to Newark for the funeral, and could I give him a ride to the service in Connecticut? I said sure, by corollary deciding whether I would go at all. He saved me a lot of dithering. I wanted to see my cousin, and with him I wouldn’t be going in solo. And then there was his example. “Cool cousin” earned my respect many years earlier when he came to my mother’s funeral as the lone representative of my father’s family. I’ve always considered the gesture principled and brave. My father did nothing.

The next day I was still sifting through my non-feelings about him when I received my half-sister’s email. It was a personal broadcast to most of her address book assuring everyone that “Dad died comfortably with his children at his side.” Ouch. It was a slap to be reminded directly that I wasn’t his child. Perhaps I had rejected or not earned it. I have always realized it takes more than blood to make a family. Becoming a father confirmed that. Family is in the things we do. Blood without sinew moves nothing. A branch without foliage is a naked fork in the family tree.

To be honest—as I would have been had he asked—I was agnostic about the whole thing. The relationship was “in the queue” but never seemed pressing. I did make the initial contact when I was eighteen, and not because I was looking for anything. It was actually a peevish thing: I was tired of people being surprised I’d never met my father. After my mother died, suddenly everyone was asking about him. They wanted a feel-good moment hearing he was stepping up with little orphan Andrew. I disappointed them. There was no one else either. I then found myself trying to reassure them. Very irritating.

There was often incomprehension of my indifference. Surely I must be hurt or angry or wistful or in denial. No, not really. Ironically the only reason I ever felt bad was people telling me I should feel bad—and then because I felt nothing! The doubters, sometimes desperately earnest, were incapable of turning off their emotional projection no matter what it cost me. If I got upset with them it was assumed to confirm I was upset with him. People with unexamined lives say silly things.

Anyway, the contact led to nothing of substance. So it goes. Who’s to blame? Who cares? Blame is pointless when one party is dead. It just didn’t happen. I forgive him even as I don’t think well of him. I also have to remind people that it’s not enough to have a father. You have to get one of the good ones. I don’t think he would have been a good one, though that doesn’t make me grateful for things like having to shoulder taking care of my mother in her illness alone.

As for the funeral, I had no obligation to go. He would have agreed, endorsed it even, and it would have been convenient. I’d rather watch TV than spend a half-dozen hours on the interstate. But I am not him. I did what I thought was right, not diluting my rules to match his. He was my father no matter what he thought of his son. The opportunity to pay my respects would not come again. I had an incidental purpose: I went to claim my name. I am a Douglass, not an afterthought. Others may share my name, but none of the clan can separate me from it.

The following week the big day came and I forgot to go. I completely forgot. I didn’t even have clothes packed. At the time I was often foggy about the day of the week let alone the agenda, but this was a unique oversight. The whole thing simply slipped my mind as if it hadn’t been there in the first place. I was three hours from the airport and completely unprepared. I was working on a roof thinking about shingles or nails or whatever banalities when out of the blue (from my point of view) my cousin called on my cellphone about the pickup.

I think forgetting his funeral was the most damning thing I ever did towards my father. I couldn’t have ever said something so dismissive. It’s not the mistake but the underlying detachment. His funeral rated a zero in my mental planner.

My cousin however is not a zero. By amazing grace or dumb luck, some part of his plane broke at the gate. Their departure was delayed several hours. He apologized and insisted he would not inconvenience me. He would rent a car. I was aghast at what I’d done but admitted nothing. I stared at my phone, still standing on that roof, and struggled to do the math and logistics quickly. “Oh no,” I said, “I insist. No problem, I’ll see you there.” It was oh-so-easy to be a gracious.

I apologized to everyone—no one in my circles had been dwelling on the event either—and sped out of town. I made it to the airport right on time even with a detour into Pennsylvania to pick up a high voltage Jacob’s Ladder (someone’s ex-science fair project) that I bought off eBay for my sideline in science. My cousin was so nice. He apologized again. I told him not to worry about it, and I really meant it. Please let it go. I was very charitable. I was embarrassed as hell. I didn’t confess the truth for years, then earning one of the best double-takes that I can remember.

We arrived late at night at a hotel where the family had taken out rooms. My reception was tepid. I had figured on being something of a black sheep, but not an invisible sheep. There was a half-dressed cousin who gave no greeting. I met my half-brother for the first time. I can’t recall him saying a word to me—but then who knows what about me he’d heard from our father. Perhaps my rampant leprosy. I saw my cousin’s father, an uncle who had been very kind about visiting me over the years; unfortunately his mind had largely failed him and we said nothing. The next day I also met a half-sister who seemed very nice, and saw her sister with whom I’d had a falling out over, appropriately enough, the interpretation of our father’s history. The girls were from his third marriage, the one that stuck.

For me it was all good. I was glad to have made it. I kept the poker face.

The service the next day was quiet. I’m sure people said nice things. I hope he was more memorable than the eulogy. I remember only the recessional of bagpipers skirling out Amazing Grace. It must be conceded that Amazing Grace on the pipes is a triumph. Played especially well or badly it can make a hard man cry, thanks to a quintessentially Scottish instrument that harmonizes a kazoo and an electrocuted cat. Disappointingly, the pipers didn’t wear the Douglas(s) tartan. I’m not picky about these things, but my clan, whose name means dark or perhaps blood river, does have a kickass history not to mention a fine-looking tartan.

As for the service, I saw no tears but perhaps it was the way of the WASP, known for its dissembling and lack of stingers. It might have been his impassive legacy. Certainly he was not a bad man, and rebuttals to eulogies are given in private. Here the intrigue was at the reception.

“So how are you related to Bill?” I was asked. Strangers making polite conversation.

“I’m his son.”

“Why, I never heard he had another son!” they said. Strangers being stupid.

Another son. Yes, the secret spare. I was amused as I watched them swirling their cocktails uncertainly. It was his bad not mine. He hadn’t mentioned me to friends he had known for decades. I can understand why. It would lead to awkward questions, and he was smooth. To him I was a historical footnote. Water under the bridge. Now it was dropped into their laps under the influence of alcohol, the great fogger of the confused.

I wish I’d thought to say, “Sure, he’s around here somewhere,” but it didn’t matter. I was in a pleasant post-libation mood. I’m ethnic enough to enjoy a scotch, the more so if I didn’t pay for it. I talked longer than I wanted to an avuncular older gentleman who had much to share about life, the universe, and everything. He delivered a flood of inebriated insights with great gestures of an ice-rattling highball, the kind where you lean back and wish for a raincoat. Still he was a companionable man and I came away knowing him better than the fellow we’d just planted in the ground.

It took a long time after this event before I figured out what exactly bothered me about the death. It’s the finality. Death is unforgiving. While I might not dwell on the past, the problem is that he and I have no future. That possibility was the only thing I had in him. Almost certainly neither of us would have endeavored for more—two stubborn men plus 38 years is solid precedent. Yet now that the door has been slammed shut, there is also the death of possibility. Once again the choice is no longer mine.

Beautiful piece of writing.

LikeLike

What a kick ass writing. Thanks so much for sharing.

LikeLike

Hi, I don’t know what to say except, as the others above – excellent writing, on an obviously difficult topic. I really enjoyed reading it.

LikeLike